De Agostini/Getty Images

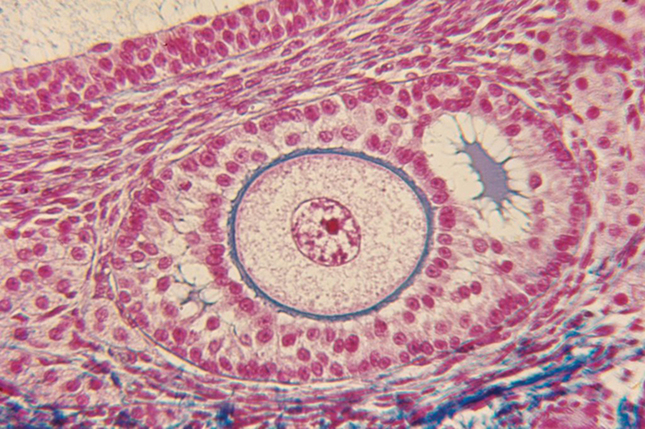

A section of human ovarian follicle seen under a microscope.

View full image

De Agostini/Getty Images

A section of human ovarian follicle seen under a microscope.

View full image

Michael Marsland

Kutluk Oktay, head of the Laboratory of Molecular Reproduction and Fertility Preservation Medicine, is exploring delaying menopause.

View full image

Michael Marsland

Kutluk Oktay, head of the Laboratory of Molecular Reproduction and Fertility Preservation Medicine, is exploring delaying menopause.

View full image

For many women in their fifties, menopause can mean a lot more than hot flashes and mood swings. Key hormones plummet during menopause, and women’s risk of ailments such as osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease increase drastically. One hundred years ago, when women barely lived past their fifties, they might not have noticed anything different. Times have changed. Women now often remain active in their careers, families, and communities well into their seventies or eighties.

Although science has extended human lives by decades, “menopausal age didn’t move,” says Kutluk Oktay, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility expert and an adjunct professor at the School of Medicine. “It’s time to proportionally expand menopausal age.” The average age of menopause in North America is 51, and prior research suggested to Oktay that delaying this might reduce the risk of age-related chronic diseases.

One possible solution may lie in a technique that Oktay developed 25 years ago: ovarian cryopreservation and transplantation. During this procedure, surgeons remove and freeze part of the ovaries, and then transplant the tissue back into patients years later. Oktay initially designed this procedure to preserve fertility in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. But transplanting young ovarian tissue also reintroduces estrogen and other hormones whose presence could stave off menopause.

Oktay and his team have now devised a mathematical tool to estimate how long ovarian cryopreservation can delay menopause for healthy women. These predictions, published in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, suggest that most women between the ages of 21 and 40 would be able to delay menopause by at least a few years—and with an earlier start, the delay could be upwards of ten years.

The model incorporates key variables that determine the number and quality of egg-bearing follicles in an ovary, including the person’s age, the amount of ovarian tissue collected and frozen, how well the tissue survives the transplant process, and whether the transplant is carried out in multiple procedures. This can guide physicians to the optimal amount of tissue for freezing. Sometimes, less is more. For example, the model recommends removing less ovarian tissue for people with lower ovarian reserves—which might not only push back the start of menopause, but also extend childbearing years.

Oktay hopes to use patient data to confirm the accuracy of these predictions and make the tool even more useful for physicians advising their patients on the benefits of this procedure. “Right now, I’m using it with my patients,” he notes.

In Oktay’s eyes, menopause isn’t the enemy. “Menopause is not a disease,” he says. “It is one of the manifestations of aging.” By pushing menopause back, he hopes to reduce the burden of aging-related diseases, allowing women to live longer, healthier lives.

loading

loading