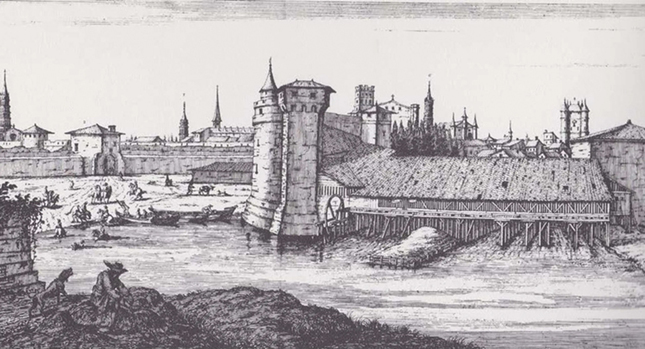

The Société des Moulins de Bazacle in Toulouse, France, a milling company founded in the twelfth century.

View full image

The Société des Moulins de Bazacle in Toulouse, France, a milling company founded in the twelfth century.

View full image

Up early on a Saturday, you’ve been to your Jazzercise class. With a Starbucks hot chocolate secured in the cup holder of your Ford, which you had serviced yesterday at JiffyLube, you’re on your way to your local Home Depot. On the way home, you’ll pick up cat food at Petco, check to see if your glasses are ready at Pearle Vision, and grab some bagels from Bruegger’s Bagels for tomorrow’s brunch.

Welcome to corporate America.

“Most of the world’s business takes place in the form of corporations,” says William N. Goetzmann, Edwin J. Beinecke Professor of Finance and Management Studies at the Yale School of Management. “How did such a powerful economic force arise”?

Recent research by Goetzmann and two French colleagues has upended the convention that joint stock companies (JSCs)—precursors to the modern corporation—suddenly appeared at the turn of the seventeenth century in northwestern Europe with the emergence of the English East India Company in 1600 and the Dutch East India Company two years later.

Instead, Goetzmann says, the team presents a thesis of multiple, independent JSCs developing centuries earlier. “The need for a stable structure that would allow for the raising of large amounts of capital was present way before the seventeenth century,” Goetzmann says.

As with the biological theory of convergent evolution, where similar adaptations appear in unrelated species (they use the example that insects, birds, and bats all developed the ability to fly through independent evolutionary paths), the researchers note the emergence of corporate forms from a variety of sources. They show that what we recognize as the current publicly traded corporate form—a legal entity that allows people to purchase and transfer shares while limiting shareholder liability—is identifiable in enterprises including mills in twelfth-century Toulouse in southern France and polders (low-lying land reclaimed from the water and protected by dikes) in twelfth-century Holland.

The practice of dividing assets, rooted in Roman inheritance law, was a foundation for the emergence of JSCs, allowing, Goetzmann notes, “for the inheritance of shares rather than having to split up the castle.”

The paper was published in Business History.

Goetzmann says corporations are likely here to stay, but expects to see different corporate forms develop over time. “The corporation is a tool that can be used for good or bad,” he says. “At their worst, corporations have perpetrated evils from slavery to deadly pollution. At their best, they are mechanisms for generating and sharing in economic growth.”

loading

loading