Chris Buck

Turner Brooks ’65, ’70MArch, seen through a floor-level window in the urethane foam structure he built in 1968 on the Yale Nature Preserve.

View full image

Chris Buck

Turner Brooks ’65, ’70MArch, seen through a floor-level window in the urethane foam structure he built in 1968 on the Yale Nature Preserve.

View full image

Courtesy Turner Brooks ’65, ’70MArch

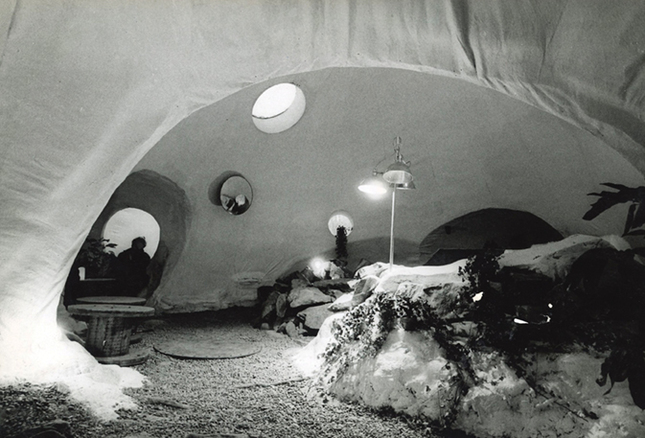

The foam house soon after its completion. For a few months, the house was the subject of media interest and the site of at least one party.

View full image

Courtesy Turner Brooks ’65, ’70MArch

The foam house soon after its completion. For a few months, the house was the subject of media interest and the site of at least one party.

View full image

Chris Buck

Brooks, seen inside the collapsing structure, says more of it has fallen down each time he’s seen it in the last year and a half.

View full image

Chris Buck

Brooks, seen inside the collapsing structure, says more of it has fallen down each time he’s seen it in the last year and a half.

View full image

Courtesy Turner Brooks ’65, ’70MArch

The burlap “balloon” that was inflated to form the structure was painted and became the house’s interior surface.

View full image

Courtesy Turner Brooks ’65, ’70MArch

The burlap “balloon” that was inflated to form the structure was painted and became the house’s interior surface.

View full image

Courtesy Turner Brooks ’65, ’70MArch

Openings were cut in the foam to make the porthole-like windows.

View full image

Courtesy Turner Brooks ’65, ’70MArch

Openings were cut in the foam to make the porthole-like windows.

View full image

Chris Buck

Although it’s still an odd thing to come across in the woods, the ruin seems less jarring than the original white plastic structure must have been.

View full image

Chris Buck

Although it’s still an odd thing to come across in the woods, the ruin seems less jarring than the original white plastic structure must have been.

View full image

Turner Brooks and I aren’t lost, exactly, but we aren’t sure how to get where we’re going. We have parked his VW Jetta by the side of the road and walked into a hilly patch of woods, taking advantage of trails when we can and stomping across rocks and tall grass otherwise. I’m regularly checking Google Maps on my phone to compare the little blue blob that shows where we are to the red pinpoint that represents my rough estimate of our destination.

Brooks (’65, ’70MArch) has been in these woods before, once in the recent past and, before that, more than 50 years ago. He knows what we’re looking for. About a mile in, we spot it atop a small hill: a curved, rust-colored . . . well . . . object, kind of sculptural, vaguely organic, gathering moss, and falling apart almost before our eyes. We stop to take it in.

“As a ruin, it just seems so much more empathetic, less alien,” Brooks says. “It seems to be now part of the space of the forest.”

What we’re looking at are the crumbling but surprisingly persistent remains of something Brooks designed and built in 1968, when he was a student at the architecture school: an experimental structure made of urethane foam. It’s a souvenir of a moment when social consciousness and optimism about technology led students to experiment with a new way of making architecture.

“A guy a year ahead of us, Bill Grover [’69MArch], saw a Union Carbide ad demonstrating the making of a little igloo-like structure,” Brooks recalls. “And the structure looked like a balloon covered in urethane foam, sprayed out of the nozzle of a gun which combined a resin and an activator in the nozzle. After it sprayed out, it expanded immediately, 30 times its original volume, and became rigid. Bill Grover thought this would be a great thing to bring to students at Yale to design experimental domestic structures.”

The idea was in keeping with a new spirit of hands-on learning at the architecture school. Two years after becoming chair of the architecture program in 1965, architect Charles Moore had launched the first-year building project, in which students design and build a project for the public good. It continues to this day as the Jim Vlock First Year Building Project.

Union Carbide donated some of its product to the school, and a class led by Professor Felix Drury took up the challenge. After a class competition, three designs were chosen to be built in the Yale-owned woods just west of the Yale Golf Course. One of the three was Brooks’s, a biomorphic, curvilinear collection of domes with a long narrow entry tube. It was an evolution of an earlier design he called the “wombulus tombulus.”

The students sewed lengths of coated burlap cloth together to make the inflatable structures that would be sprayed with urethane; they used leaf blowers to inflate them on site. Once the space was enclosed, they cut openings in the lightweight structure and installed clear plastic windows.

Building the foam structures was pretty much an end in itself; there was no plan or practical way to use them for anything. Brooks’s was used for at least one party that fall, but the buildings were more or less forgotten. Brooks says the other two, which were much closer to the golf course, become an annoyance to golfers and were soon destroyed by the golf course staff. (He says they first tried to burn the structures, but stopped when they realized how toxic the smoke was.)

But because it was a little further removed, Brooks’s foam house was spared. After a year or two, he returned to see how it was faring. “I walked in through the tube, and about six naked hippies went rushing through the building and then leapt through this back window and ran out.”

Beneath the whimsical designs of the foam houses, the students had some serious ideas about the potential of the construction method. Because the foam only expands on the reaction of two substances that can be stored in canisters, and because the balloons could be folded into compact shapes, the elements for building such a structure could be contained in a small package. “The idea was that we could arrive at a site that needed housing, maybe only with a helicopter, and drop down this high-density, low-volume package,” Brooks says. The houses could be built quickly and cheaply.

The students’ professor, Felix Drury, went on to design and build several foam houses, and a handful of others were built around the country. After graduating, Brooks and his classmate Dan Scully ’70MArch were approached by a contractor who was interested in the concept. He hired them to tour the country in a rented Piper Cub airplane to visit other foam houses on a kind of fact-finding mission. In the end, it became apparent that the material’s weak structural properties and toxicity were fatal flaws.

Brooks moved on to a career as an architect in Vermont, designing vernacular-inspired wood buildings that are aesthetically about as far away from a plastic igloo as you can imagine. (He designed Yale’s Gilder Boathouse in Derby, Connecticut.) He began teaching at Yale in the 1980s and moved to New Haven in the 1990s.

Will Suzuki ’23, a New Haven native who is currently studying architecture at the University of California, Berkeley, was one of Brooks’s students. Brooks taught the senior studio in the undergraduate architecture major until he retired in 2023, and Suzuki was in his final class.

One Wednesday evening in 2022, Brooks convened the class in a seminar room in Paul Rudolph Hall to share stories about his journey in architecture, accompanied by a slide show with some of his work. Among the slides were a few pictures of Brooks’s foam house in its heyday, full of people. “He was sure that it had crumbled and was long gone,” Suzuki says.

But while the house was all but forgotten to most people, it was well known among local mountain bikers. The woods have become a popular place for biking, and they are now criss-crossed with trails.

One of those bikers, fortuitously, is Suzuki’s older brother Andrew. He and his comrades were well acquainted with the ruin on the site; they used it as a landmark for navigation. (“Turn left at the foam house.”) In the fall of 2023, Andrew took Will and their parents on a Thanksgiving hike in those woods.

When Will saw the ruin—although it looked very little like the slides he had seen—it all came together. “I sent Turner a picture saying ‘Is this the foam house?’ and he wrote me back ‘Holy crap!’”

A few months later, Suzuki and another of Brooks’s students, Jenny Coyne ’23, took their teacher into the woods to be reunited with his creation. “We had only really seen these hazy photographs from the sixties,” Suzuki says. “We all kind of fell in love with the ruinous state of it.”

“It was magical, beautiful, and serendipitous,” says Coyne, “characteristic of the types of experiences that Turner taught us to notice and appreciate in the world: gentle interactions of light with form, critters making homes in unlikely places, and ruins that might even exceed their original designs.”

The ruin shows what happens to a foam house left to the elements. Brooks believes the center of the roof eventually collapsed after sagging under the weight of snow and ice. The foam, once an off-white shade, has somehow taken on the color of rusted steel. It’s not just weather that has conspired against the house; there are several holes that appear to have been drilled by woodpeckers (who were likely very confused), and human visitors to the site have broken off pieces and etched graffiti on the walls.

Really, though, it’s maybe more remarkable that the house has held together as well as it has, considering its fragility and the human penchant for vandalism. Its remoteness may have helped. The woods where it sits feel like a kind of no-man’s land: Are they part of the Regional Water Authority’s Maltby Lakes property to the south? Or an extension of the Yale Golf Course to the east? There are no signs on the property, and the only point of entry is a small opening in a fence on Fountain Street, obscured by a utility box.

In fact, the 200-acre tract where the house sits is called the Yale Nature Preserve. Established in 1925, the preserve is the property that was left over after the golf course was carved out of a 700-acre parcel given to Yale in 1923 by Sarah Wey Tompkins, widow of Ray Tompkins, Class of 1884. Set aside for research and education, the preserve is managed by the Yale Natural Lands Committee. Faculty use it for research into plants, trees, soil, and amphibian life, but Yale does not promote its use by the public. It is not mentioned on university websites, and there are no maps or guides available. Besides protecting plant species and wildlife, the preserve has done a pretty good job of protecting a wombulus tombulus for 57 years.

Brooks fears that the ruin’s decline is accelerating; he sees more collapsed sections every time he visits. With its days seemingly numbered, it might be time to get going on a vision he had when he first saw the ruin. “I want to see it as a stage set for events integrating music and dance,” he says, “where ancient Druid friends would add to the ritual, especially at night under a full moon.” If he gets that off the ground, we’ll be sure to share the pictures.

loading

loading

1 comment

Turner - I was in the Yale class of 1964. Your were in the class of 1965. I only remember you because we both played intramural hockey and you were good, whereas I s-cked.

Anyhow, I believe that you and Dan Scully (a NH resident and son of my favorite professor at Yale, Vin Scully), were both Yale Architectural graduate school classmates of my brother Jan Van Loan (Brown, class of 1996?).

you can reach me at vanloaneugene3@gmail.com