Yale Alumni Weekly

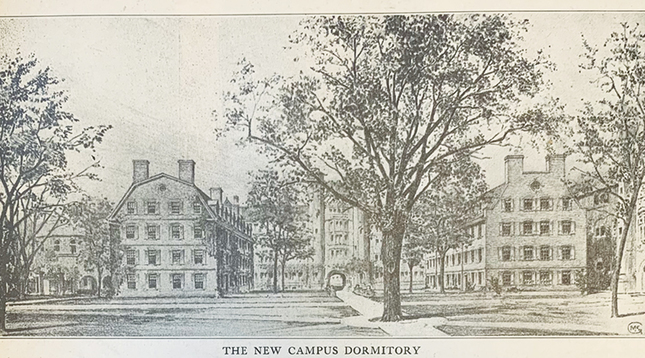

This rendering of

McClellan Hall (at right,

with Connecticut Hall at

left) appeared in the Yale

Alumni Weekly shortly after

construction began.

View full image

Yale Alumni Weekly

This rendering of

McClellan Hall (at right,

with Connecticut Hall at

left) appeared in the Yale

Alumni Weekly shortly after

construction began.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives

On the McClellan Hall construction fence, someone painted “For God, for country, and for symmetry.”

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives

On the McClellan Hall construction fence, someone painted “For God, for country, and for symmetry.”

View full image

Mark Alden Branch ’86

Mark Alden Branch ’86

In the 1920s and ’30s, Yale razed more than two dozen of its own buildings and embarked on a massive program of new construction that established the look of the university we all know. It may seem surprising that the biggest fight over reshaping the campus centered on Edwin McClellan Hall, an unassuming 56-bed dormitory on the Old Campus. But the battle over McClellan in the fall of 1924 was about more than aesthetics. It also raised the question of who was to run the university—the faculty, the alumni, or the trustees.

After World War I, Yale made new efforts to transform itself from a provincial college to a modern university, and the growing pains were many. Alumni and faculty noted with some discomfort that the board of trustees, the Yale Corporation, had evolved from one dominated by Congregational ministers to one full of business leaders. Further, as the workings of the university became more complex, an administrative body had begun to make decisions that once would have been made by the faculty.

On October 23, 1924, students living on the Old Campus woke to find workers removing elm trees and excavating in the southwest corner of the quad, in front of Linsly-Chittenden Hall. They soon learned from talking to the workers that a new dormitory was to be built there, one similar in shape, size, materials, and style to Connecticut Hall in the southeast corner.

This was news to nearly everyone at Yale, and a chorus of disapproval rose immediately, led by the Yale Daily News, which called the plan a “desecration” of the campus. Students, faculty, and alumni raised three main objections. First, the building’s placement within the quad would disrupt the open space. Professor Henry Beers, Class of 1869, told the News that the Old Campus was “the largest college quadrangle in this country or in England” and that “its broad sweep should not be broken.” Second, the duplication of Connecticut Hall, the university’s oldest building and the only remaining Colonial structure on campus, was seen as an absurd and fussy attempt at balance. (A graffito on the construction fence surrounding the site read “For God, for country, and for symmetry.”)

And finally, the lack of communication was seen as overreach by the university’s trustees and administration, who should have consulted with the faculty and alumni before proceeding. As the News put it, “It has appeared to many who have the affairs of Yale at heart that the physical property of the university has become the property of the Corporation, and that the faculty has come to be regarded merely as its employees.” The move to begin construction without any notice struck opponents as an effort to avoid objections; because of the apparent secrecy, the News and the campus took to calling the building “Hush Hall.”

More than 500 students—about a sixth of undergraduates—signed a student petition calling on the university to suspend construction “until graduate opinion shall have been consulted.” While at first rejecting this request, the university did offer more information.

The building, it turned out, had been proposed by the university’s Committee on Architectural Plan, led by architect James Gamble Rogers, Class of 1889, to make a small dent in the student housing shortage and to balance Connecticut Hall as part of a larger plan for the campus. It was also suggested that McClellan would help hide Chittenden Hall—then seen as old-fashioned and unsightly—from the quad.

Motivated to have more on-campus housing in place by the fall of 1925, the committee had moved quickly. They secured the trustees’ approval for the site in May, hired an architect (Walter B. Chambers, Class of 1887) in early September, and presented his final plans to the trustees later that month. Yale College dean Frederick Jones, Class of 1884, opined that the faculty would approve of the plan, which the trustees took as an endorsement when they okayed the project in October, but Jones had not in fact consulted the faculty. The university had been preparing a public announcement, but as President James Rowland Angell explained in a letter to the Alumni Weekly, “the wholly unforeseen promptness of the builders resulted in their beginning work before the material for the press was ready.”

On November 8, after continued bashing in the News, the trustees agreed to suspend construction so that the committee could hear from the Yale community. Records show that both the faculty and the Alumni Advisory Board were deeply divided about the new building, but in the end, once they were given a voice, each body voted to support whatever decision the trustees made.

Construction resumed on December 14; a few days later, students staged a mock cornerstone-laying that reenacted the entire controversy, with participants dressed as “spirits of symmetry,” “undercurrents of dissent,” “Mother Connecticut,” and a winged angel representing the president.

The name Hush Hall persisted into the spring, as shown by a June 1 memo in the university archives from an official in the treasurer’s office to one in the bursar’s office: “We are having a number of bills come in from local tradesmen for material delivered to ‘Hush Hall’ It has occurred to me that probably [an employee] is ordering material and giving that address, and I wish you would caution him not to circulate the name among tradesmen of the town.” But by the time the hall opened to students in the fall, it had a formal name. Helen Livingston McClellan, the widow of Edwin McClellan, Class of 1884, made a gift so that the building would be named for her husband, who had died in 1924.

McClellan has undergone renovations more than once in its hundred years, and it has served as temporary office space for the history department and as isolation housing during the Covid-19 pandemic. Today it functions as annex space for residential colleges, in keeping with its original purpose of housing undergraduates.

loading

loading