loading

loading

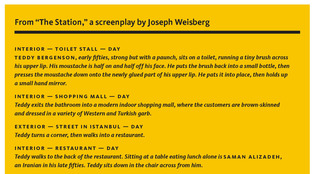

Spymasters Excerpt from "The Station," a screenplay by Joseph Weisberg. View full image

Espionage realist Joseph Weisberg was intending to be an English major,with vague writerly plans, when he happened upon Ivo Banac’s course on the history of the international Communist movement. “It was one of those experiences that you actually go to college for,” Weisberg recalls. “That course really lit me on fire. I also took Wolfgang Leonhard’s course on the history of the Soviet Union, and those classes turned me into a cold warrior. Leonhard offered a nuanced view of foreign relations, but I came out of it with a very un-nuanced view of the world. I wanted to fight in that war.” And he did. Although there was no attempt to recruit him on campus—“I think they had stopped doing that”—Weisberg called and asked for an application to the CIA a couple of years after graduating, when he found himself trapped in a desk job in Chicago. “I didn’t want to work behind a desk, so I looked up the CIA in the phone book, and they sent me this huge envelope with the application. It included this ballpoint pen with the inscription ‘CIA: Interesting Careers for Interesting People.’” The rest is, well, secret history. Weisberg is discreet about his three and a half years at the Agency, saying only that he was training for a foreign assignment that he never embarked on. “The Farm,” the Agency’s training camp at Camp Peary, Virginia, crops up a few times in An Ordinary Spy, which is the story of a fledgling mission gone wrong. Here protagonist Mark Ruttenberg is chatting with his station chief:

A major conceit of Weisberg’s novel is that it is a work of nonfiction submitted to the CIA’s Publications Review Board to avoid the disclosure of classified information. (Weisberg did submit the manuscript to the PRB, but most of the inked-out deletions are his own.) So, in describing an officer’s trip to collect a new recruit, Weisberg is “required” to black out potentially sensitive passages:

The fictional setting for An Ordinary Spy seems to be a generic Third World military dictatorship, not far from the Equator. But it’s never disclosed. In Weisberg’s telling, the modern spyscape wasn’t just ordinary; it was surprisingly bureaucratic, especially to someone raised on spy fiction. “I had a fantasy of joining the CIA since I was a little boy,” he says. “I read all the John le Carré novels when I was 12 years old. That world was enormously appealing to me. I unconsciously related to the loneliness involved, and of course there was some intellectual prowess required. God, was that romantic. Beat up the bad guy, figure out an enormously complex puzzle, realize you’d been screwed, then retreat to some quiet place to be moderately unhappy for the rest of your life. Yes! I wanted that!” But reality bit: “After working in the CIA, I learned that le Carré’s depiction of the intelligence world was as false as Ian Fleming’s James Bond version. It was all bullshit.” When Weisberg sold An Ordinary Spy to the movies, his literary agency asked if he might want to write for television. “I was working full-time as a teacher and as a novelist,” Weisberg says. “This seemed to be a way that I could write and make money, which, as you know, is a rare and happy confluence of events.” Weisberg wrote a pilot for FX called The Station, about the CIA station in Sofia, Bulgaria. Now he’s working on another, The Americans, about a family of KGB “illegals” living in Falls Church, Virginia, during the Reagan administration. The “Jennings” family was inspired by the real-life illegals flushed from their hideaways in New York, Boston, and Virginia last summer—Russian agents who had been living undetected in the United States for decades, with the help of ultra-deep-cover gear like karaoke systems and diet pills. “Their whole life is pretending to be Americans,” Weisberg says. Should the children attend Yale? I suggest, during our lunch in lower Manhattan. Perfect cover … Weisberg rolls his eyes. “Maybe they will apply.” It seems unlikely.

|

|