loading

loading

Spymasters Excerpt from The Secret Soldier by Alex Berenson. View full imageKeeping faith Alex Berenson’s thrillers focus on the war against Islamic terrorists, in part because he knows the territory. The tall, intense motorcycle enthusiast has embedded himself with US forces in Iraq and in Afghanistan three times—as a New York Times reporter and as a note-taking novelist, to absorb the look and feel of the wars that his protagonist, John Wells, has been fighting for a decade. Wells, a Montana native, converts to Islam during his decade-long mission infiltrating al Qaeda. “He loved the Koran’s exhortations that men should treat one another as brothers and give all they could to charity,” Berenson writes in his 2006 debut novel, The Faithful Spy.

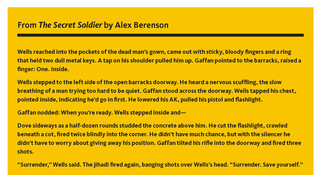

This is fiction, mind you; Berenson describes himself as a not particularly observant Jew. He says a freshman survey course on the history of Islam piqued his interest in the religion. His books include—packed in among the international intrigue and explicit violence—thumbnail sketches of real and highly topical issues: the difference between Sunni and Shiite Muslims, the beginnings of fundamentalism in the House of Saud. The friction in the books between matters of faith and generous use of M-16s and Beretta pistols, as well as messier weapons, gives Berenson a character with depth. John Wells remains a Muslim even after killing innumerable coreligionists. (“All the guys we go after—it’s not like they’re Buddhists,” a colleague sardonically notes in The Secret Soldier.) But, Berenson says, Wells “has a real problem with his faith. He finds it hard to believe in the existence of God, and he finds it hard to remain faithful while living a life of violence. The tension tears at him.” Or, as The Secret Soldier puts it:

In The Faithful Spy, we learn that John Wells’s history of violence includes his days on the Dartmouth football team. Wells “broke the leg of the Yale quarterback,” Berenson writes. “He had not felt remorse.” Ouch. A few years ago, when a fan asked him just how realistic his novels were, Berenson invoked the old joke about two men being chased by an angry bear: “I don’t have to outrun the bear—I just have to outrun you.” Translation: it’s not so important that a grizzled CIA veteran thinks I’ve got it just right; it’s more important that you, the readers, think so. Berenson is quite candid about what he does and does not know about Spyworld. Although he has spent plenty of time on US military bases overseas, and had many conversations with special ops agents like Wells, he hasn’t embedded with them; “those are the guys you catch a glimpse of, walking around outside the wire.” He cheerily allows that he has never set foot in CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, although all his novels have scenes set there. Which is not to say Berenson is a slouch on the research front. He traveled to Russia to research locales for The Silent Man (2009), about a “loose” post-Soviet nuke, and he attended FBI seminars held for Hollywood screenwriters. (He was a consultant for the Fox network hit 24.) He has also visited the super-spooky National Reconnaissance Office headquarters, where the defense department, the CIA, and other agencies coordinate international satellite surveillance. Here, one of Wells’s colleagues searches extremely high-resolution NRO satellite photos, looking for a camouflaged jihadi camp:

Berenson is now tackling his sixth John Wells thriller. Wells has been enough of a commercial success that Berenson kept him in business, but, he says, “I can’t say I intended to write six books about the same guy. I’m tired of war. I’m sick of the war in fiction, and I’m sick of the war in real life. But it’s always going to be with us. It’s always going to be there to write about.”

|

|