loading

loading

Arts & CultureYou can quote themWitticisms Mark Twain never made. Yale law librarian Fred R. Shapiro is editor of the <i>Yale Book of Quotations</i>.

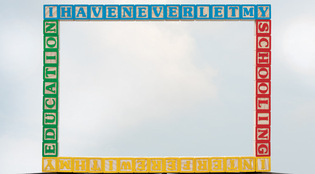

Photo illustration: John Paul ChirdonView full image

In my last column I referred to Mark Twain as a “quotation magnet,” meaning someone to whom quotations are attributed inexorably, regardless of whether there is any truth to the attribution. My fellow quotation scholars have used different terms for the phenomenon. Ralph Keyes, author of the wonderful books The Quote Verifier and Nice Guys Finish Seventh calls the pseudo-sources “flypaper figures” because quotations stick to them. Nigel Rees, compiler of the estimable Brewer’s Famous Quotations and Cassell’s Movie Quotations, among many other works, has coined “Rees’s First Law of Quotations”: “When in doubt, ascribe all quotations to George Bernard Shaw.” He is also responsible for the phrase “Churchillian drift”—the attribution of grandiose or belligerent sayings to Winston Churchill. The preeminent American quotation magnet was Twain. Witty and mildly cynical remarks of all sorts are routinely credited to him. After all, this was the man whose genuine quotable lines include “Whenever you find that you are on the side of the majority, it is time to reform”; and “In the first place God made idiots. This was for practice. Then He made School Boards.” Twain is irresistible quotation flypaper. “Golf is a good walk spoiled” is attributed to Twain on 263,000 websites, according to Google. But the earliest use I’ve found was printed three years after Twain’s 1910 death: on December 19, 1913, the Stevens Point (Wisconsin) Daily Journal noted—without identifying an author—“Golf, of course, has been defined as a good walk spoiled.” The excellent website Quoteinvestigator.com has listed another non-Twain variant from 1903. The earliest linkage to the great humorist that I discovered was in Reader’s Digest, December 1948. As I’ve recorded in the Yale Book of Quotations, a number of other leading pseudo-Twainisms also have impossibly late dates for their first known Twain attribution. “I am an old man and have known a great many troubles, but most of them never happened” was credited to Twain in Reader’s Digest, April 1934. But a similar quip, assigned to an anonymous octogenarian, had appeared in the Washington Post on September 11, 1910. Reader’s Digest, obviously the headquarters of the Twain attribution industry, also quoted him in October 1946: “I have never let my schooling interfere with my education.” Quoteinvestigator.com has shown that this witticism was circulating long before RD added Twain’s name: a prior version, which doesn’t mention him, exists from 1894. Then there is the famous “If you don’t like the weather in New England, just wait a few minutes.” Bennett Cerf credited Twain with this in his 1944 book Try and Stop Me. But an earlier version, with no attribution, was printed in the Washington Post on March 4, 1934, in reference to Washington, DC: “Just wait five minutes for a change—That’s what the weather here will do.” My own favorite apocryphal Twain comment is this poetic remark, whose Twain lineage began in 1949 with Evan Esar’s Dictionary of Humorous Quotations: “Twenty-four years ago I was strangely handsome; in San Francisco in the rainy season I was often mistaken for fair weather.” The real Mark Twain, after a succession of tragedies late in life, expressed opinions so bitter that they rarely get repeated. Here is an example from the story “Little Bessie”: “God made man, without man’s consent, and made his nature, too; made it vicious instead of angelic, and then said, Be angelic, or I will punish you and destroy you.” Perhaps it is no surprise that most people prefer to remember his gentler lines, even those that were not really his.

The comment period has expired.

|

|