Protesters don’t usually protest with string instruments, a washboard, and an overturned washtub. But this photo was taken in 1969, and the SDS Scuffle Band--shown here kneeling in front of Woodbridge Hall--was trying its best to end Yale’s ROTC.

View full image

Protesters don’t usually protest with string instruments, a washboard, and an overturned washtub. But this photo was taken in 1969, and the SDS Scuffle Band--shown here kneeling in front of Woodbridge Hall--was trying its best to end Yale’s ROTC.

View full image

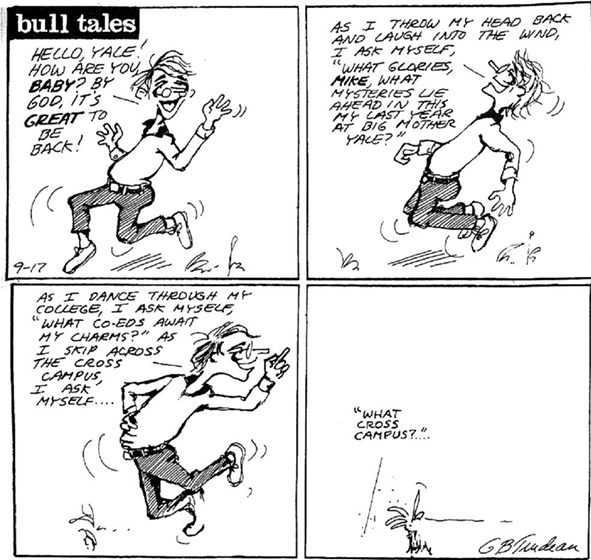

G. B. Trudeau

Trudeau’s early comics were hilarious from the start. After he studied at the Yale School of Art, his drawings became much more fluid—and just as entertaining. He received an honorary degree from the university in 1976.

View full image

G. B. Trudeau

Trudeau’s early comics were hilarious from the start. After he studied at the Yale School of Art, his drawings became much more fluid—and just as entertaining. He received an honorary degree from the university in 1976.

View full image

It was a perfect autumn afternoon in 1969, the beginning of my first year at Yale. The photograph I took, rediscovered more than 50 years later in a folder of negatives, captured an iconic moment in American cultural history, and a transformative one for me. The event was a protest against Yale’s ROTC, the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, the college-to-military program then under attack nationwide for directly linking campuses to the war in Vietnam.

Students for a Democratic Society—the leftist group—was leading the protest on the steps of the administration building. What seemed extraordinary to me was that they weren’t reciting the usual “Hey-hey, ho-ho” antiwar chants, or waving picket signs. They were singing, and accompanying themselves on banjo, fiddle, washboard, and washtub bass. They introduced themselves as the Yale SDS Jug Band, or at least that’s how I remembered the scene. But when I look back now at my Class of 1973 yearbook, one former bandmember (Laurie Chevalier ’73, on washboard) called it the Yale SDS Scuffle Band, a nice play on the musical term “skiffle” that also hinted at a willingness to engage as needed in short, disorganized street fights.

In my memory, they performed only a single number, sung in calypso mode, and the words of the chorus have stuck in my head ever since:

I’m talkin’ ’bout R-O-T-C,

Keepin’ all the people in slav-e-ry,

Whether you’re black, white, yellow, or brown,

You’re gonna be glad when we shut it down.

I was hooked, as a budding leftist, and took several photos of the scene. It appealed to me partly because the protest sought a highly specific, if largely symbolic, step against a war most of us had come to regard as immoral and illegal. By late 1969, more than 35,000 Americans had died in Vietnam, including over two dozen former Yale students, most of them officers. Vietnamese dead, civilian and military, ran deep into the hundreds of thousands.

That protest was my first encounter with what became, for me, one of the more useful lessons of a college education, though maybe a trivial one in the circumstances: I was impressed by the value of thinking imaginatively and keeping an edge of wit in all things. I was also wowed by the talent on display. I had an SDS friend at Fordham who could rant with the best of them about Trotskyites. But musically? He’d been tossed out of his high school band for barely knowing the D from the G string on bass. These Yale lefties, on the other hand, could pitch and hit.

One other thing caught my eye. A small group of counterprotesters stood just off to one side, evidently enjoying the music, if not the message. One of them held up a sign: “DON’T PUSH! It’s going anyway.” Yale had in fact already announced the end of its ROTC program. But to protect the scholarships of the handful of active members, Yale chose to delay the actual shutdown until the 1972 graduation. At the time, most of us in the crowd rolled our eyes at the lameness of this counterprotest, as well as at Yale’s gradualist approach. The part of me that lives in a new century wishes all right-wing protests could be this tame, or at least this law-abiding. Also that all leftist protests could be this entertaining. What really impresses me now, though, is the civility and the mutual tolerance on both sides. It seems like such a piece of another time, another century.

An email chain led me to Chuck Cohen ’70, who’s playing 12-string guitar in the photo. He assured me that they weren’t singing “The ROTC Calypso” at that moment, because his chord fingering didn’t match that song, and the steel drum was missing. (And what about the atomic kazoo?) Then-lead singer Mark Zanger ’70, who wrote “The ROTC Calypso,” emailed to explain that they were definitely singing a traditional number, “Pity the Downtrodden Landlord.” (“Please open your hearts and your purses, / To a man who is misunderstood.”) That was the only reason they would be down on their knees, for the mock-lachrymose begging at the end of the song. The SDS Scuffle Band, it turns out, had an entire leftist repertoire, plus occasional histrionics.

But let’s get to the iconic moment in American cultural history.

Zanger was then the most prominent member of SDS at Yale. At the time, he was widely believed to be the model for “Megaphone Mark” Slackmeyer—a leading character in bull tales, a cartoon drawn by Garry Trudeau ’70, ’73MFA, for the Yale Daily News. In a typical 1969 bull tales, Mark stands alone in front of the college president’s house, bellowing through his megaphone, “Alright, King, this is SDS! We’ve had enough of this R.O.T.C. and classes and authority and stuff!! DO YOU HEAR ME?” King, modeled on Kingman Brewster Jr. ’41, Yale’s politically adroit president of that time, strolls out in his three-piece suit and by the fourth panel has smooth-talked Mark into quivering inanition.

A few months after graduation, Trudeau was sharpening up both his art and his wit, and turning bull tales into Doonesbury, for syndication in newspapers. (Mike Doonesbury, a leading character in the cartoon, was modeled on Trudeau himself.

Doonesbury combined the name of Trudeau’s roommate, Charles Pillsbury ’70, with a slang word meaning, roughly, “clueless boob.”) Doonesbury quickly became a national phenomenon, and characters who had formerly wandered the Yale campus strode the national stage via the funny pages of more than 700 US newspapers. (“Funny pages,” noun: archaic term from a time when newspapers, printed on actual paper, used to devote a page or more every day to comic strips.) The comics, as they were also known, served as essential relief from the grim stuff in the news, and a welcome stop en route to the sports pages. Readers followed them faithfully, and rarely complained if the comedy lapsed into the comfortably insipid.

Doonesbury changed that, introducing political savvy and wit to the funny pages, and enraging some readers. Newspapers at times felt obliged to drop the strip for a day, or slide it over onto the editorial page, due to references to sex, drugs, crime, or all of the above in the lives of various government officeholders. Doonesbury became a must-read commentary during the Watergate scandal and the downfall of the Nixon administration.

In one famous strip, from May 29, 1973, Mark Slackmeyer, having traded in his megaphone to become a radio host, delivers a sober account of the alleged crimes of John Mitchell, the attorney general of the Nixon administration. “It would be a disservice to Mr. Mitchell and his character to prejudge the man,” Mark declares in the third panel, “but everything known to date would lead one to believe he is guilty!” Then his eyes go wide with lunatic fervor and he declares, “That’s guilty! Guilty, guilty, guilty!!”

Trudeau was then producing Doonesbury from a dorm room at the top of an entryway in Farnam Hall on the Old Campus, where he served as a freshman counselor while completing his MFA at the Yale School of Art. But the cartoon strip was already moving beyond its original Yale setting and cast of characters into a more adult world. “The trip from draft beer and mixers to cocaine and herpes is a long one,” Trudeau explained in the early 1980s, “and it’s time they got a start on it.” The list of characters expanded with the news, at times including Vice President Dan Quayle depicted as a feather, Congressman Newt Gingrich as a bomb with a lit fuse, President Bill Clinton as a waffle, and California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger as a groping hand.

Trudeau’s targets often felt the hit. After Doonesbury satirized George H. W. Bush ’48—Ronald Reagan’s vice president at the time—as having placed his manhood in a blind trust, Jeb Bush marched up to Trudeau at the Republican National Convention and snarled, “I have two words for you: walk softly.” More manfully, but in the third person, journalist Hunter S. Thompson once threatened to rip out his four-panel tormentor’s lungs.

As the cast of characters changed, and the lit fuses sometimes exploded, Megaphone Mark Slackmeyer endured. He got an on-air job at National Public Radio, came out as gay in the 1990s, and went through a marriage and a divorce—all before the Supreme Court decision that recognized same-sex marriages. (If there was a scandal, it had to do with his marrying a conservative Republican.) Today, Slackmeyer remains a gray-haired guiding presence at NPR, where Trudeau has had cause to reprise that “guilty! Guilty, guilty, guilty!” panel, first during the Reagan Administration Iran-Contra scandal, and again during a 2017 investigation of another president Slackmeyer tended to identify as “that Jackass.”

The original Megaphone Mark—Mark Zanger—has also endured. He has had a career as an editor and food writer, has written cookbooks, and still leans left. (One reader called his 2003 American History Cookbook “history seen through the eyes of the hungry.”) “While in college,” he concedes, “I was foolish enough to act like a cartoon character, and that helped inspire Megaphone Mark.” But he is reluctant to take too much credit: Mark Rudd, his SDS counterpart at Columbia University, made the front page of the New York Times then and may also have played a part.

Zanger suspects Trudeau, “like any artist,” does “not want to be restricted by having a character be somebody in particular. As he went along, he modified characters away from any original models.” For instance, Brian Dowling ’69, a Yale quarterback and the original model for Trudeau’s B.D., did not serve in Iraq and lose a leg, as B.D. did. That was only a plot twist at a time when Trudeau was focusing on injured veterans. And Zanger would never have married a conservative Republican. Trudeau himself has never shown much interest in these “who’s who” questions. His characters, he has said, are items in the toolbox, to be pulled out and put to work in the service of the story.

In any case, it’s all slipping away into history. Since 2014, Trudeau has produced new cartoons only on Sundays, and Doonesbury’s clout has waned accordingly. Chuck Cohen, the 12-string guitarist in the SDS Scuffle Band, recalls that when he taught religious history at the University of Wisconsin, he could buy credibility with new students by telling them he was not, as rumored, the original model for Zonker Harris, Doonesbury’s dreamy, druggy slacker-in-chief.

Then one day, a student raised his hand and asked, “What’s ‘Doonesbury’?”

___________________________________________________________________

In our print magazine, and in an earlier version of this article online, we included a bull tales cartoon that included a homophobic slur. We have removed it here, and we apologize for its inclusion.

loading

loading

4 comments

-

Richard O’Brien ‘80, 1:45pm July 12 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Kerry Fowler, 1:44pm July 18 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Theresa Hamacher, 1:45pm July 19 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Geoffrey Richard Tanner, 6:09pm August 18 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.Fun, informative piece. But why, out of all the “bull tales” strips you could have chosen to illustrate it, did you go for one featuring an anti-gay slur? Yes, the term was more “accepted” in the early ‘70s, but to run it today, with no acknowledgement, seems incredibly tin-eared and insensitive.

One of our McClellan entry mates had joined the Party of the Right in our first days at Yale. One evening he was expecting party members to pick him up to go to a meeting. He had second thoughts and panicked so we hid him in a back bedroom when they came to the door. I recognized the leader as the short guy sporting a Hitler hairstyle I saw walking around campus with a posse. I've always thought that he was the inspiration for Doonesbury's Chase Talbott III.

Glad to see Richard O'Brien's comment here, though I'd be more negative. An anti-gay slur may have been more accepted in the 1970's, but it was never right, and it certainly isn't "hilarious," to use the term that the author uses. I'd also note that the strip doesn't limit itself to just one slur. . . women are abused here, too.

I, for one, am very tired of the uncritical nostalgia for a Yale gone by that this article exemplifies. If we're going to talk about the past, we should be honest about the bad that accompanied the good.

I believe that the magazine should pull this article and apologize for the amazing lack of judgement.

I was just discussing this very article with a friend and roommate of mine from the Yale class of 1995, whom I was visiting in Milwaukee. He and his wife have a (very happy and well-adjusted) gay son and (at least) one other non-binary-identifying child, whom they support unconditionally. My friend hadn't read this particular article yet, but I shudder to think of what his family would think of Yale--long a welcoming and inclusive (and safe!) place and space for LGBTQ+ students, faculty, and staff; and a place my friend recalls with great fondness--if they had happened to stumble across this article, prominently featuring the "F-word" in the featured comic-strip panel in this retrospective on Garry Trudeau's work.

Worse, as Theresa Hamacher notes, the comic panel is also misogynistic.

To cap it off, a gold medallion inset notes: "Doonesbury introduced political savvy and wit." This particular selection from Trudeau's work is neither savvy nor witty.

Disappointing.

The article itself is a fun, informative read, badly marred by this exercise in poor judgement in the selection of illustrative examples from Trudeau's opus. I agree fully with M. Hamacher that an apology is due; perhaps keep the article (minus the offending cartoon) but annotate it with a clear, cohesive, and comprehensive explanation of why readers may have found the content offensive and insensitive?