When I was young, my family traveled a great deal, and one of those trips took us to Maine. I was about ten years old and completely gullible. We happened to see a restaurant called The Silent Woman. Its logo was a drawing of a woman wearing an old-fashioned dress with puffy sleeves and an apron and carrying a serving tray. However: she had no head. I studied the drawing carefully, trying to find out what it meant. Was it important for women to keep silent?

Those were the years when most middle-class married women in the US performed all the homemaking, cooking the meals and keeping the house clean, so that their husbands could work on the important things. Then came the glorious uproar of the women’s rights movement, and for many women, life became far more livable.

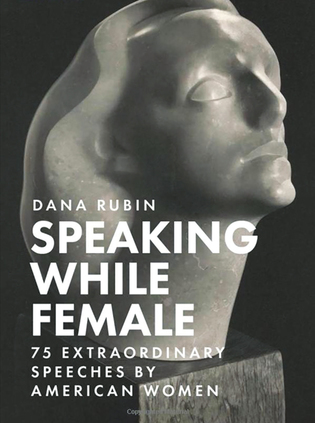

But the 1960s and ’70s were only one short span of rebellion. Brave and fervent women have been speaking out for ages, as Dana Rubin ’82 shows us in a new book: Speaking While Female: 75 Extraordinary Speeches by American Women. In the introduction, she notes that whenever she gives talks, or teaches classes on public speaking, she asks her listeners to name some famous American orators. Immediately, the audience starts listing names of distinguished men. Then she asks for names of women, and the audience blinks and stays quiet. On a good day, someone might remember Michelle Obama or Hillary Clinton ’73JD.

Which is why, Rubin writes, she has “searched in institutional repositories, history books and biographies, journals, old newspapers, and out-of-print books”—urgently seeking to save women’s speeches before they crumble into dust. And her results are fascinating.

In Speaking While Female, Rubin introduces each speech with a single page of explanation, so that readers will have some understanding of the when, where, and why of that particular woman’s era and subject. Rubin begins with Anne Hutchinson, who was tried for heresy in 1637. Hutchinson was steadfast, declaring, “If you do condemn me for speaking what in my conscience I know to be truth, I must commit myself unto the Lord.” For the book’s finale, Rubin chose the 2021 commencement address of the University of Southern California, which was delivered by Bina Venkataraman of the Boston Globe: “People think of courage as entering the arena. . . . But sometimes courage is just quietly asking, ‘Why not?’ a million times.”

Among the book’s 75 names, some are very well known: Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, Ida B. Wells, Isadora Duncan, Shirley Chisholm, Sandra Day O’Connor, Michelle Obama—the list goes on. But there are many others most of us have never heard of. The third speech in the book is by Nanye’hi, a Cherokee born around 1738. She was a warrior and a negotiator, but only one small scrap of paper remains from an original speech she gave. “Our cry [is] all for Peace. . . . Let your women’s sons be ours; and let our sons be yours.”

Another woman, Frances Thompson, lived through the Memphis riots of 1866. She had been a slave, but was then working as a tailor and laundress in a house she shared with a younger woman. Thompson told the Congressional committee investigating the riots that seven men had come to their house and gang-raped and robbed them both. A decade later, doctors examined Thompson and found that, anatomically, she was a man. She was arrested for cross dressing and required to work on a chain gang. She died after a few months. Rubin writes, “We are indebted to her for courageously speaking out . . . and demonstrating human dignity.”

Rubin’s choices of women to write about include Dolores Huerta, who founded the National Farm Workers Association with César Chávez; Martha Jane Sara, a Native Alaskan who championed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act; Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, Helen Keller, Gloria Steinem, Oprah Winfrey, and many, many more. It is the kind of book you can pick up at any time, settle down with, and learn something entirely new.

Finally, a personal note: I’m glad to say that it wasn’t long before my young self realized that The Silent Woman was an obnoxious joke. Even better, The Silent Woman was shut down in the mid-1980s.

loading

loading