loading

loading

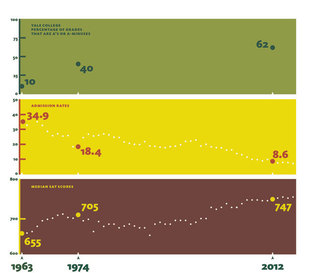

featuresGrade expectationsFifty years ago, ten percent of Yale College grades were A’s or A-minuses. Now it’s 62 percent. A faculty committee thinks that number is too high. Robert McGuire is a writer and writing teacher in New Haven and the editor of MOOC News and Reviews.  Barry FallsView full image“Once you look at the numbers, you can’t quite believe grade inflation has gotten as bad as it has,” says Tina Lu, a Yale professor who chairs the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures. “Things have gotten to a point where it seems something really ought to be done.” For Lu and her fellow members of the Yale College Ad Hoc Committee on Grading, the numbers speak for themselves: in spring 2012, 62 percent of all grades at Yale College were an A or A-minus, compared with 10 percent in 1963 and 40 percent in 1974. But some students and faculty argue that a more consistently excellent student body is responsible for at least part of the rise. This fall, the Yale College faculty will consider the committee’s recommendations for changes to the grading system. Yale College dean Mary Miller ’81PhD decided to form the committee in 2012, when she heard that a 3.8 grade point average was the cutoff for Latin honors (cum laude and above), which are limited to the top 30 percent of the class. “When Dean Mark Schenker stood up to read these numbers, I said, ‘Let’s study what’s going on here.’” Miller remembers. “Let’s begin the conversation that has been quite conspicuously absent. Surely an academic institution like ours has the responsibility to study the kind of decisions it may be making, especially when they might not be fully articulated.” The committee presented its report to faculty in April. In addition to documenting the rise in the number of A’s and A-minuses over the last 50 years, the report includes data supporting the conventional wisdom that grades are higher in the humanities. But recent increases are more prominent in the natural sciences, where the mean is up 0.22 points on the 4.0 scale between 1999 and 2012. In some departments, there’s almost no room left in the scale for inflation. In fact, says Lester Hunt, a professor of philosophy at University of Wisconsin–Madison who edited the book Grade Inflation, inflation is a misleading metaphor. “Unlike money, grades are a closed system,” he says. “There is a highest grade, but there’s no such thing as a highest price, so what happens is, as grades go up, they get squished at the upper end.” And the ad hoc committee prefers to keep the focus on compression rather than inflation. “It would be the same problem if 68 percent of the grades were C-plus or B-minus,” says economics professor Ray Fair, the chair of the committee. “You still wouldn’t have the ability to separate out the really good students from the okay but not great students, because almost everybody is getting the same grade.” Besides making it harder to recognize outstanding performance, the committee maintains, grade compression discourages students from working their hardest, “muddies the effectiveness of grades as signals to outside organizations,” and, because of different standards across disciplines and departments, may unduly affect students’ decisions about what courses to take.  Chart: Mark Zurolo ’01MFA. Sources: Yale Book of Numbers, Office of Institutional Research.Yale College hasn’t publicly released year-by-year data on grades, but the report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Grading provided numbers for 1963, 1974, and 2012. We also show here the increase in SAT scores and the decrease in the admission rate for classes during the same period. SAT scores are an average of math, verbal, and, since 2010, writing scores. (The SAT was “recentered” in 1995 to make 500 the median, so scores in 2000 and later are 30 to 40 points higher than they would have been before recentering.) View full imageIn its April report, the committee proposed four changes to remedy the situation. Two of them were approved by the faculty with no controversy: to encourage discussion about grading policies in each department by requiring chairs to submit a report to the Yale College dean annually about those policies; and to distribute data to faculty every year on the average grades in every department (as was the practice before 1982). Two other proposals, though, encountered more resistance. The first is to “exchange the currency” by converting from the familiar letter grades to a number system in which passing work is scored between 60 and 100. The second is to establish non-mandatory guidelines for departments to follow, with the hope of spreading grades along the following curve: 35 percent of grades in the 90–100 range, 40 percent in the 80–89 range, 20 percent in the 70–79 range, and 4 or 5 percent in the 60–69 range; 0 or 1 percent would be failing. (All failing work would be assigned a grade of 50 under the number system.) As the ad hoc committee prepared to present recommendations to faculty, it started running into opposition from students who objected to both the numerical grading system and the grade distribution guidelines. Through the Yale College Council, students appealed to faculty to send the two proposals back to the committee, arguing that rising grades were not necessarily a sign of relaxed standards. “There’s been a cultural change, with a huge emphasis on achieving competitive grades, that didn’t exist 40 years ago,” says YCC president Daniel Avraham ’15. “There are several natural trends that contribute, and it isn’t just that professors are too generous.” Some faculty are skeptical of the argument that current students are simply more capable of A-level work. “Sheer nonsense,” says engineering professor Alessandro Gomez. “Nothing remotely like that is the case,” says philosophy professor Shelly Kagan. (Gomez and Kagan have reputations as being among the toughest graders on campus.) But English professor Leslie Brisman, who has taught at Yale since 1969, thinks that students on the whole do better work today. “I can think back 40 years to students I thought of as ‘gentleman’s-C’ types. I don’t have any of those now,” says Brisman. “It’s been so long since I’ve had even one student who seemed to be coasting or just wanted to pass the course. The lower range just isn’t there anymore.” Calhoun College master Jonathan Holloway ’95PhD, a professor of history, African studies, and American studies, thinks Yale’s greater selectivity may play a role, but he also points to another cultural shift: students today are more apt to lobby their professors for better grades. “Students are much more aggressive about grade grubbing,” says Holloway. “That’s a symptom of people not learning from an early age about failure. When I was playing little league soccer, you only got a trophy if you won. Nowadays, everybody’s getting trophies.” Some speculate that the rise in grades results from pressure on faculty from anonymous student evaluations, but the historical data don’t confirm that. Grades climbed sharply at Yale and elsewhere in the 1960s, a fact that is sometimes attributed to faculty helping students maintain their draft deferments during the Vietnam War era. But during the 1970s, when Yale started using student evaluations, grades remained level at about 40 percent A’s or A-minuses. Instead, grade inflation may feed on secrecy. The annual report on grade distributions by department was no longer sent to the faculty after 1982—which is approximately the year when grades renewed their steady climb. It is this kind of report that the committee proposes be distributed again. But even if more of today’s undergraduates are doing excellent work than in the past, committee members say, there must still be differences among those who are getting A’s—but faculty have no way to indicate that. “We’re attempting to color with only three crayons in the box,” says Lu. The numerical scale, with its 90–100 range for A grades, would allow for distinctions. Lu knows students don’t like it. “You actually hear students say things like, ‘It would mean that people would have to work as hard as they could in every course.’ I would hope that’s part of what you’re here to do. It’s not hard to imagine there are students who are working to get a low A because that actually maximizes your results without a great outlay of effort. There are fairly obvious ways in which it’s undermined what we think of as the mission of Yale College.” Students opposed to the proposals make their own version of the values argument. Simon Brewer ’16, who authored a letter to the committee that was co-signed by 45 freshmen, says, “Yale admissions used as a major selling point that Yale students are fundamentally more happy. It’s an atmosphere where students are very much focused on learning together rather than beating each other on the curve the way they do at places like Princeton. That’s absolutely one of the reasons I chose to attend Yale.” That argument has some merit to it, according to Richard Kamber, a professor of philosophy at the College of New Jersey, who has written several articles on grading in higher education. Since Prince-ton adopted the goal of reducing A’s in 2004, he says, students there have come to believe they are graded more harshly than their Ivy League peers. “There’s no real data to show that Princeton students have suffered in terms of admission to professional schools or getting the kinds of jobs they aspire to,” Kamber says. “There is a perception that a significant percentage of them are disgruntled. They say, ‘Maybe we should go to Yale instead.’” But Kamber, an advocate of grading policy reform, says that the solution is for others to follow Princeton’s lead. “This can be thought of as a leadership issue,” he says. “It’s been pretty much a lone enterprise on Princeton’s part. For Yale to join Princeton in trying to have a more coherent policy regarding grade distribution would be a feather in the cap of the university.” As for making the Yale environment more competitive, Fair says that’s in the nature of grading: “If you have less compression, some students are going to get lower grades than they otherwise would. That’s independent of numbers or letters. The least competitive environment would be one in which the university had no grades at all.” Some faculty are skeptical about whether the proposed changes would be effective. “If we all end up giving just as many 90s as we are currently giving A’s, then there’s no advantage,” says Kagan. “That has to go hand-in-hand with the suggested percentages, which still struck me as overly generous. I’m dubious about whether the number system will work, but it’s not as if I have some better proposal up my sleeve, and I’m certainly eager to give something a try.” The committee’s recommendations seem to have been held up less by doubts about the proposals than by the perception that students didn’t have enough input. Fair notes several points where the committee heard from students—but Avraham says it was too little and too late. Early in the process, a few students met with the Dean’s Advisory Committee; but the meeting was confidential, he says, so those students couldn’t share what they learned. And a three-hour public forum, with 80 students in attendance, was held after the recommendations were drafted and four days before they were presented to faculty for a vote. Kagan, the perennially tough grader, says he went into the faculty meeting ready to vote for the proposals. But because of the student objections, he ended up making the motion to send the proposals back to committee. “It’s not that I think the student concerns are necessarily correct,” he says. “I’m inclined to think they’re probably not. But I came away thinking that it hadn’t been handled the way it needed to be. It’s too big of a change to rush through.” The committee—with students added to the roster, says Miller—is scheduled to report to the faculty again in November, though a vote on recommendations may take longer. “Every department will have a conversation and will talk about their standards and about how they determine what their grades should be in their program,” she says. “This college-wide conversation is a critical step. Nothing is more important than having the data and beginning to talk about why we assign the grades we do.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|