loading

loading

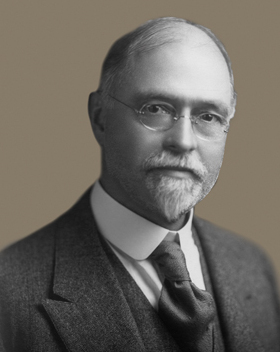

God and white men at Yale Manuscripts & ArchivesIrving Fisher (1867–1947), who spent his career at Yale, devised many of the basic concepts for analyzing the modern financial system. He was also one of the leading figures promoting eugenics as national policy. View full imageOther Yale eugenicists also allowed their work to be distorted by the cause. Robert Yerkes is remembered today as a primatologist and the founder of the Yerkes National Primate Research Center at Emory University. But when he came to Yale in 1924, as a professor in the new field of psychobiology, he was better known for developing the first national program of intelligence testing—a program that provided an ostensibly scientific basis for the fight against immigration in the early 1920s. Yerkes and a team of like-minded scholars had designed the test at the start of World War I, as a means “for the classification of men in order that they may be properly placed in the military service.” By war’s end, the US military had administered it to 1.7 million recruits. According to the test, the average native-born white American male had a mental age of 13. But his foreign-born counterparts were morons (a label coined by the eugenicists, from the Greek for “foolish”), with an average mental age barely over 11. Yerkes wrote to key congressmen during the immigration debate to remind them of what Army testing had said about the inferiority of southern and eastern Europeans. Fisher chimed in. “The facts are known,” he declared. “It is high time for the American people to put a stop to such degradation of American citizenship, and such a wrecking of the future American race.” In truth, the facts were badly flawed, and Fisher had reason to know it. Yerkes’s test, which supposedly gauged innate intelligence, was mainly a measure of how long a person had been in the United States and perhaps also how well he might fit in at the local country club. Among the questions asked: “Seven-up is played with A. rackets, B. cards, C. pins, D. dice.” “Garnets are usually A. yellow, B. blue, C. green, D. red.” “An air-cooled engine is used in the A. Buick, B. Packard, C. Franklin, D. Ford.” Fisher received a sharp upbraiding from a member of his organization’s own immigration committee over “the shakiness of the evidence” used in its lobbying. Herbert S. Jennings, a geneticist at Johns Hopkins University, resigned from the AES in 1924, citing its “clearly illegitimate” arguments. Privately, he advised Fisher that a eugenics society was no place for serious researchers, whose work depends on freedom “from prejudice and propaganda.” Fisher had been lobbying the federal government for eugenicist policies since at least 1909, when his final report for Theodore Roosevelt’s presidential commission on Americans’ health and longevity devoted a chapter to the “question of race improvement through heredity.” He had been fighting to limit immigration since 1914, when he coauthored a report to the American Genetic Association. It declared that “steamship agents and brokers all over Europe, and even in Asia and Africa, are today deciding for us the character of the American race of the future.” Fisher’s friend, Madison Grant, likewise wrote about “being literally driven off the streets of New York City by the swarms of Polish Jews.” Grant became the leading advocate for state laws mandating involuntary sterilization of the “unfit” and banning interracial marriage. He also persuaded Virginia to discard its practice of granting the privileges of a white person to anyone with 15 white great-grandparents; state officials were soon sniffing out and harassing anyone with even “one drop” of non-white blood. Fisher, Grant, and the AES wanted to restrict both the number of immigrants and their nationalities. They argued that each foreign country’s annual quota should be proportional to its representation in the United States as of the 1890 census—that is, before the flood of new immigrants had entered the country. Using an outdated census was a way to discriminate against southern and eastern Europeans and thereby to ensure, as Fisher put it in the New York Times, “a preponderance of immigration of the stock which originally settled this country.” The Immigration Act of 1924—with quotas based on the 1890 census—became law that May. Congress had been “hoodwinked” by the eugenicists, Representative Emanuel Celler complained, with the result that total immigration was cut in half, and immigration from targeted countries like Italy by as much as 90 percent. The law would later become a factor in preventing Jewish refugees from escaping Nazi persecution. In Germany, an imprisoned political extremist viewed these developments with satisfaction. Writing Mein Kampf in his cell, Adolf Hitler complained that naturalization in Germany was not all that different from “being admitted to membership of an automobile club,” and that “the child of any Jew, Pole, African, or Asian may automatically become a German citizen.” Now, though, “by excluding certain races” from the right to become American citizens, the United States had held up a shining example to the world. It was the sort of reform, Hitler wrote, “on which we wish to ground the People’s State.” Nazi Germany would soon become the dark apotheosis of eugenics. When compulsory sterilization began there in 1933, the Nazi physician in charge of training declared he was following “the American pathfinders Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard” (author of The Rising Tide of Color against White World-Supremacy). Eugen Fischer, the leading Nazi eugenicist, would thank Grant and his racial theories for inspiring Germans to work toward “a better future for our Volk.” As early as 1933, the New York Times was noting that if you changed Madison Grant’s “Nordic” to “Aryan,” his arguments sounded much like “recent pronouncements and proceedings in Germany.” Even so, eugenicists put Grant’s name forward four times in those years for an honorary doctorate from Yale. University officials gave his backers the polite brush-off. Other eugenicists also backed away. When Ellsworth Huntington became president of the AES in 1934, membership was shrinking. He was obliged to lay off staff and move the operation into his university office, in a mansion at 4 Hillhouse Avenue (since demolished). The harsh, coercive measures with which eugenics had made its name were likely to raise hackles in the shifting politics of the 1930s, says Brendan Matz ’11PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in history at the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia. So Huntington began to promote a milder brand of reform eugenics. Nevertheless, when he was organizing a conference in 1936, Huntington asked a researcher who had recently returned from Germany to report on the Nazi sterilization program. “In the face of the present psychological situation, it is not wise to laud Germany,” Huntington advised, “but it is perfectly legitimate to say that in spite of certain mistakes Germany is also doing things which are desirable.” By then, Fisher himself had stopped campaigning publicly for eugenics, and no longer tried to work the notion of the nation’s racial stock into economics discussions. His old ally Madison Grant died in 1937, and Fisher seemed to recognize the alarming effects of their earlier efforts together. In 1938, he joined three other economists in attacking the radio personality Father Charles Coughlin, a notorious anti-Semite, for adding “fuel to the already blazing flames of intolerance and bigotry.” A year later, he was one of the signatories to a public letter issued by Christian and Jewish institutions, cautioning Americans “against propaganda, oral or written” that sought to turn classes, races, or religious groups against one another. The letter warned, poignantly: “The fires of prejudice burn quickly and disastrously. What may begin as polemics against a class or group may end with persecution, murder, pillage, and dispossession of that group.” Fisher survived World War II, dying in 1947 at the age of 80. His major causes by then were warding off deflation and requiring banks to hold larger reserves against their deposits, proposals that remain relevant in the post–Lehman Brothers era. We do not know how Fisher, Yerkes, Huntington, or other eugenicists responded to the discovery of Auschwitz, Buchenwald, and other centers of racial hygiene. No doubt they were horrified. Grant’s Passing of the Great Race would turn up once more after the war, at Nuremberg. Hitler’s personal physician Karl Brandt had been charged with brutal medical experiments and murder in the concentration camps. His lawyers introduced Grant’s book into evidence in his defense, arguing that the Nazis had merely done what prominent American scholars had advocated. Brandt was found guilty and sentenced to death. We know better now, of course. And yet eugenic ideas still linger just beneath the skin, in what seem to be more innocent forms. We tend to think, for instance, that if we went to Yale, or better yet, went to Yale and married another Yalie, our children will be smart enough to go to Yale, too. The concept of regression toward the mean—invented, ironically, by Francis Galton, the original eugenicist—says, basically: don’t count on it. But outsiders still sometimes share our eugenic delusions. Would-be parents routinely place ads in college newspapers and online offering to pay top dollar to gamete donors who are slender, attractive, of the desired ethnic group, with killer SAT scores—and an Ivy League education. Irving Fisher and the other Yale eugenicists would no doubt rejoice that the university’s germ plasm is still so highly valued—at up to ten times the price for other colleges. But if they looked more carefully at the evidence, they would discover that these highly desirable donors are now often the grandsons and granddaughters of the very immigrants they once worked so hard to eliminate.

The comment period has expired.

|

|