loading

loading

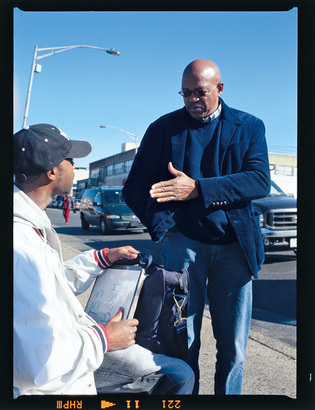

featuresMan on the streetHow a sharecropper's son deciphered the code of the city. Julia M. Klein is a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia.  Mark OstowElijah Anderson holds a streetside conversation on a sociological tour of Philadelphia. View full imageStrolling through Philadelphia's Reading Terminal Market, a neon-lit collage of food stands, specialty shops, and ethnic restaurants, Elijah Anderson passes two Amish merchants in white bonnets and a swirl of conventioneers, tourists, and grocery shoppers. Casually dapper in blue jeans and a navy blue sweater and corduroy jacket, he strides past Formica tables, where groups are lunching on sushi, hoagies, and enchiladas, en route to his favorite shoe shine stand. An old friend shows up unexpectedly and sits down beside him to catch up on news and gossip. The friend is white; Anderson is black. Their impromptu chat is a microcosm of market etiquette, where interracial amity is business as usual. A sociologist skilled at compressing complex interactions into pithy catch phrases, Anderson dubbed the Reading Terminal a "cosmopolitan canopy" in an influential 2004 article that he is now expanding into a book. The canopy, Anderson explains, is a refuge from the ethnocentric streets, an oasis of civility "where people can practice being cosmopolitan." Here people of all backgrounds do "folk ethnography," he says, observing and reporting on the behavior of those around them -- a less structured, less scientific version of Anderson's own m étier. Places like the Reading Terminal Market "may well be our salvation as an increasingly diverse society," he says. The Reading Terminal stop is part of a two-day trip to Philadelphia that the 64-year-old Anderson is hosting for his first-ever class at Yale, a graduate seminar called "Urban Ethnography." (He also is teaching "Urban Sociology" to undergraduates.) The aim is to show his grad students, many already embarked on their own ethnographies, the sites where he -- and one of his heroes, the sociologist W. E. B. DuBois -- did their studies. So closely is Anderson associated with Philadelphia, and especially its inner-city neighborhoods, that many of his colleagues believed it would be impossible to lure him away from his post at the University of Pennsylvania. But this past May, Anderson agreed to become Yale's William K. Lanman Jr. Professor of Sociology. Yale had, in fact, been pursuing Anderson since 1993. The former vice president of the American Sociological Association had turned down three offers, including one in the fall of 2006. When he finally said yes, "it was a shock even to me," jokes Anderson, whose books include A Place on the Corner (1976); Streetwise: Race, Class, and Change in an Urban Community (1990); and Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City (1999). In April, the University of Pennsylvania Press will publish Against the Wall: Poor, Young, Black and Male, a volume of essays he's editing that grew out of a 2006 symposium he organized at Penn. Anderson's hiring was a big coup for Yale. "It's really very straightforward," says Karl Ulrich Mayer, chair of Yale's Department of Sociology. "He's probably the most important urban ethnographer in the country, probably together with Mitch Duneier of Princeton." Yale sociology ranked only 19th in faculty quality in the most recent National Research Council survey, published in 1995. And until now, the department has lacked an authority on race and urban communities -- "clearly a major deficit," Mayer says, given that race remains "one of most important and problematic realities in this country." For his part, Duneier calls Anderson "perhaps the most important figure to have worked in the field of urban ethnography since DuBois" and "a consummate micro-sociologist," with "an ability to make deep sense of the smallest gestures, winks, nods, pauses, and inflections in the context of the larger social order." Anderson is also "a genius at articulating concepts which have been useful to other scholars in explaining the life ways of the inner city," Duneier says. "Ideas such as 'master status,' 'code of the street,' and 'streetwise,' among many others, have become part of the vocabulary of sociology." With a popular as well as academic audience, Anderson arguably has become, as W. H. Auden famously wrote of Freud, "a whole climate of opinion." When President Clinton wanted advice on stemming urban violence, Anderson was among a select group of experts summoned to the White House. Code of the Street is used in numerous college courses. But the very ubiquity of his ideas may have played a role in his departure from Penn, where he was embroiled in a lingering controversy over a colleague's book on poor, single mothers that he maintains leaned heavily, and without sufficient attribution, on his work. The dispute, which was supposed to have been settled by a private agreement, is complicated, and sociologists nationwide have clashed over the particulars. While the 2005 agreement was never implemented, Anderson, though not pleased, says he is moving on. "It's long behind me," he says. "I'm looking to new projects." Yet the imbroglio involved the very issues of race and respect and reputation he explicates so cogently in Code of the Street. Some might think that an academic star like Anderson would be insulated from the injuries of race in America. They would be wrong.

|

|